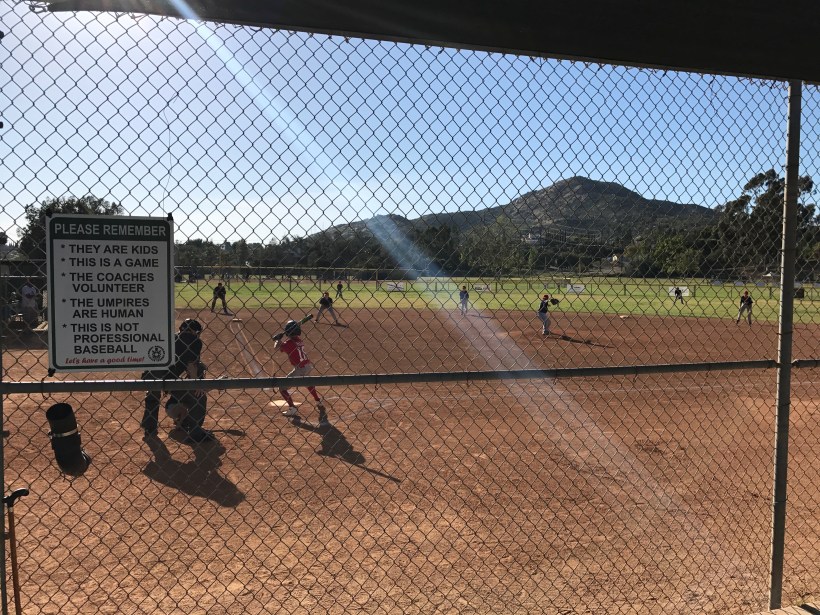

We’re in the home stretch of the Little League baseball season. Dane joined Abe and Roman on the diamond this season and once again we’ve had three boys on three teams playing twice a week since the beginning of March. Many of their games have been played at the same time making for some interesting viewing experiences. More than a few times, I’ve stood on one field managing Roman’s team while watching Abe or Dane up to bat on one of the fields across from me. I typically run the pitching machine for Roman’s ‘Rookies’ team and take my time in between each pitch to see if somebody got on base, got out, scored a run, or made a defensive play.

Sara and some contingent of the grandparents are usually rotating from field to field catching as much action as they can. What is it about these activities that compel us parents to arrange our schedules, sit out in the heat or the cold, and devote entire days to watching our kids play sports? When our kids are out on the field, we focus on their every move. We may enjoy the conversation with other parents or the time out of the house or office, but our attention is constantly pulled towards the game. A few months back Abe was playing on an off-season soccer team with group of kids from different clubs and schools that didn’t usually play with one another. The dad who organized the group was the ‘coach’ by default. At one point, I asked him if he could provide any evaluation of Abe’s ability and any suggestions about how to help him develop in the sport he loves most. The dad said, “Honestly Champ, I know Abe plays well, but I couldn’t give you anything very specific…because I pretty much only watch my kid out there.” We laughed and I appreciated his honesty. As a dad, and not necessarily a coach, he does what we all do. Watch our own kids.

We are fanatics. Sports are an unique aspect of childhood that reveals the perils and joys of love. When we love our children, what do we love? Think of how sports differ from education. For all except those who homeschool, we drop our kids off at school and have little to do with their experience. We volunteer and are happy to help with homework but that is more of a chore than a blessing. Parents aren’t motivated to watch their kids learn in the classroom, but go to a baseball practice with a team of 12 year-olds and you’ll find a bleacher full of parents…watching. A younger team sometimes require the parents to be on hand, but what compels parents to watch their middle school kids take infield or hit 20 balls off a tee into a net?

Love motivates parents to be there, to watch each drill. This love enjoys seeing our kids use their brains and their bodies, and interact with other boys and girls. It is emotionally rewarding to see them make a good play or demonstrate good character. We have heavily invested ourselves into these mini-selfs. We long for them to know the joy we’ve known in success. We know there’s lessons to be learned in the highs and lows and we want to watch the story of their little lives play out. Parents hope for a good ending. A good ending to the game, the season, their childhood. In our culture, sports are one of the main areas where parental control begins to end. Parents are tested as they have great access to observe what their kids are doing, but not much control. When we entrust our child to a coach or teacher, the chords of control loosen. But we can’t keep away from the story. We absorb every detail. This love can go awry when we don’t let go or we stay too involved. Many of us try to keep our loving hands on our children, giving a little ‘help’ from the sidelines. Of course, there may be a time and place for this, but it’s often an expression of unhealthy control instead of love. Truthfully, we want to play God in their lives, controlling the outcomes. We may fear their hurt, and want them to avoid the embarrassment of a strikeout. Our insecurities may hunger for the praise that comes from a good hit. An ‘atta boy’ or ‘atta girl’ towards our child satisfies our longing for attention, the desire for some credit for their success.

From my own experience, this control surfaced from a subconscious place and revealed what was in my own heart, regardless what I thought my intentions were. In a heated moment towards the end of a losing effort at a soccer match a few years back, I shouted at Abe to “Go!” thinking he had given up. He looked at me startled and I could tell he was instantly wounded. “I am!” he responded. Looking around at the other parents nearby, I sheepishly backed a bit off the sideline, realizing I had been exposed. I was that parent we had talked about never becoming. But if you could only see my good intentions…I wanted him to succeed, I wanted him to feel the joy of winning. What I didn’t see was how my lack of control over his play made me want to play God and make something happen for Abe where it wasn’t my place. This disordered our relationship and created hurt where I could have been a source of hope. Abe hasn’t forgotten that moment, it comes up regularly. But usually we talk about how it changed things for the better. “You guys are good sideline parents,” the kids say now. “We never hear you telling us what to do,” they say, which is our goal.

This question about parental affection is relevant to our attempts at charity as well. In our fallenness, nothing is perfect and like precious metals, our purest loves are full of impurities. As the Discovering Light team tries to love the Arsi Oromo of Southeast Ethiopia, self-evaluation is our most important task. In the world of Christian community development, the last 10 years have had a constant flow of revelation from places like Africa and Latin America where efforts at charity from the West, from governments and many churches, have caused harm and stunted progress despite good intentions. We have been shown how loving attempts to help have hurt some people because those with the wealth assumed to know what is best for those with less. Many times the poor have been treated as helpless children instead of capable partners. The effects of this are well documented in books like When Helping Hurts and films like Poverty, Inc. (which I highly recommend you watch. It’s currently on Netflix, Amazon, iTunes.)

Like the chattering parent on the sideline who believes they are helping their son or daughter, their needs and deficiencies cloud out their potential. The end result is similar.

After we finished building a well in Kalo village in 2011, the community felt they had more needs we could meet. In one encounter, a village leader asked me to consider building them a school. They had the teachers, all they needed was a building. I asked who built their homes, and the other modest but suitable structures that lined the town square. “We did,” they responded. But I got a blank stare and a shoulder shrug when I asked why they needed us to build them a school. At that moment, I wondered if we had made a mistake building the well for them. As much love we poured out raising funds and organizing the project, providing access to water had not empowered them to use the resources already available to them. I feared we had added to their sense of adequacy and saw poverty as much more in the mind than material. This has led to dramatic shift in our approach to ‘helping’ the Arsi Oromo and we have seen how important it is to encourage capacity-building without doing for them that which they can do on their own. As hard as it is to let the struggle continue, allowing growth from the inside out to take place is the most loving thing we can do.

As it is with our kids, we love them by letting them succeed and fail on the field, with an encouraging and a hopeful attitude from the sideline. When the love for our children or those in need stifles them from reaching their potential, we must let go. In a few weeks, I head back to Ethiopia to continue this effort of empowering love that will produce flourishing families and communities. My role has increasingly become one of partnering, challenging, and encouraging leaders to believe in their own God-given potential and that of the Ethiopian people. This shapes the programs we support and how we interact with leaders. I seek to protect them from unhealthy dependence on their Western partners and lowering the expectations of the people they serve. God’s purpose for them is so much bigger than they’ve ever believed and we get the joyful task of helping them see how he loves them.

For our family, the school year ends in a few weeks and we have been blessed. Marni thrived in her first year of high school with excellent grades and a Varsity letter for her place on the Dive Team. Abe navigated his way through sixth grade well, juggling new friends, sports, and spunky little brothers. Dane came into his own this year in school and we have been so proud of his responsibility and persistence (He turned 10 today! And we have only one in single digits. Yikes!). Roman is the little firecracker bouncing from one activity to the next with joy and spunk. Sara and I have been adjusting to the new challenges of the children seeking independence in their own way. As they swing from needy to self-reliant, sometimes on the same homework assignment, we are learning when to let go and when to hold on.